As the “Athens of the North” experienced a scientific awakening in the 19th century, a new discipline sought to move beyond mere herbarium specimens. Alongside rapid advances in medicine, geology, and chemistry, botany was emerging. The study of nature became part of a great intellectual movement, sparking lectures, expeditions, and public debates on the origin of life and God’s role in the ecosystem. Against this backdrop, John Balfour stood out. His name is synonymous with reforming the educational system, establishing botanical principles as a core academic discipline, and pioneering new teaching methods. He saw plants as a living part of an ordered and harmonious world, a perspective he sought to instil in his students. Read more at edinburghname.

Scottish Roots

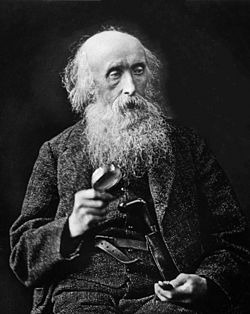

John Hutton Balfour was born in Edinburgh on 15 September 1808. He grew up at a time when the boundaries between academic disciplines were still being defined, and botany was often seen merely as a branch of pharmacy. After receiving an excellent early education at the city’s prestigious Royal High School, the young Balfour went on to study at the University of St Andrews. Following his parents’ wishes, he was initially preparing for a career in the Church of Scotland.

However, the rich intellectual environment of Edinburgh inevitably influenced Balfour’s inquisitive mind. While studying theology, he also began attending medical lectures. It was there, during his studies of materia medica, that he encountered the plant world and became instantly fascinated. The intricate structures and classifications of flora captivated him far more than religious doctrine. His academic path officially changed. This new direction led him to earn a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree in 1831.

Building Institutions

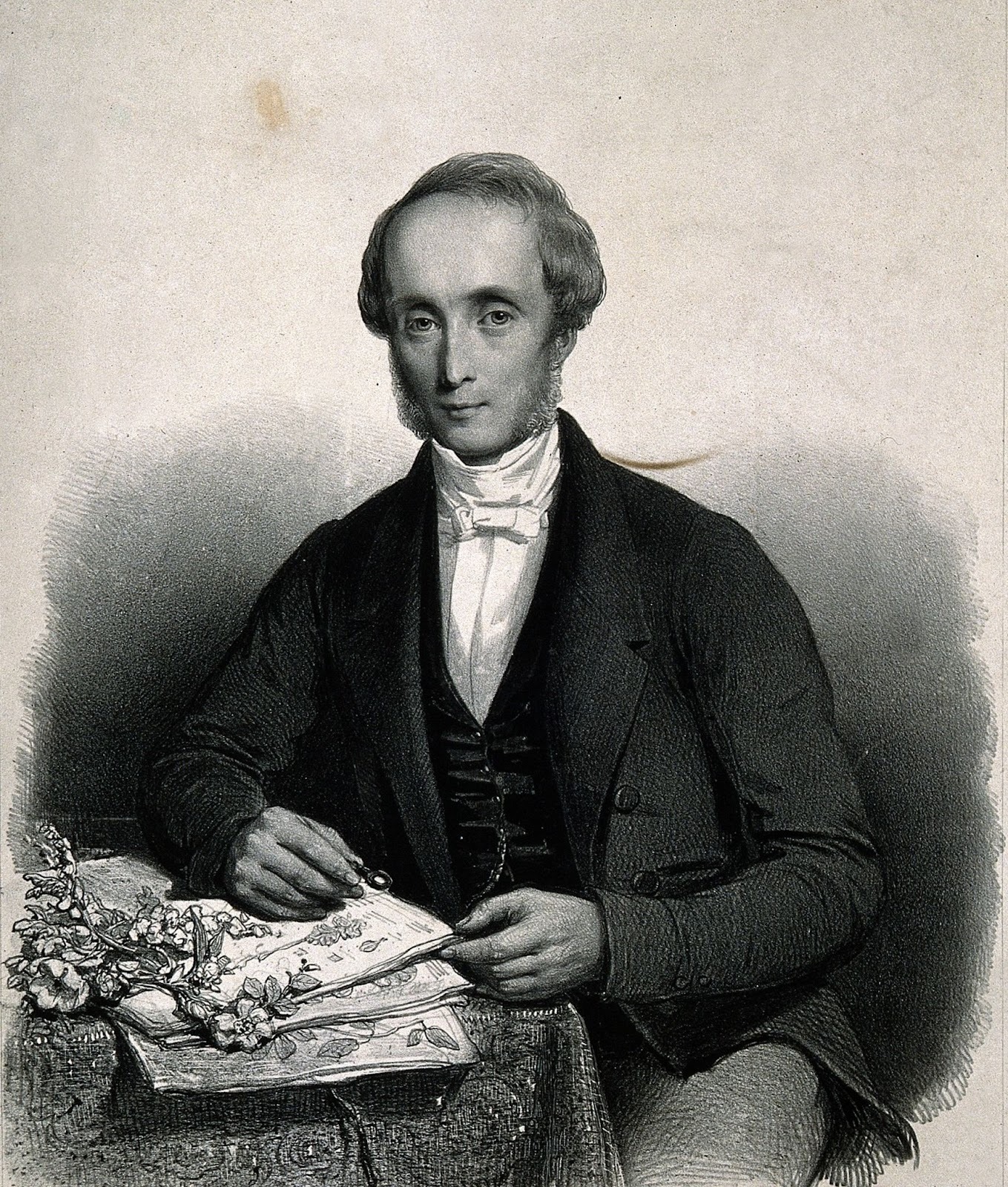

Balfour’s professional pivot was driven by a conscious mission for reform. During his student years, he had clearly observed that botany lacked structure; it remained little more than a gentleman’s amateur hobby. He believed its transformation into a fully-fledged academic discipline vitally required a strong institutional foundation. Seeing no point in waiting for someone else to take up the cause, in 1836, Balfour became one of the key founders of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh.

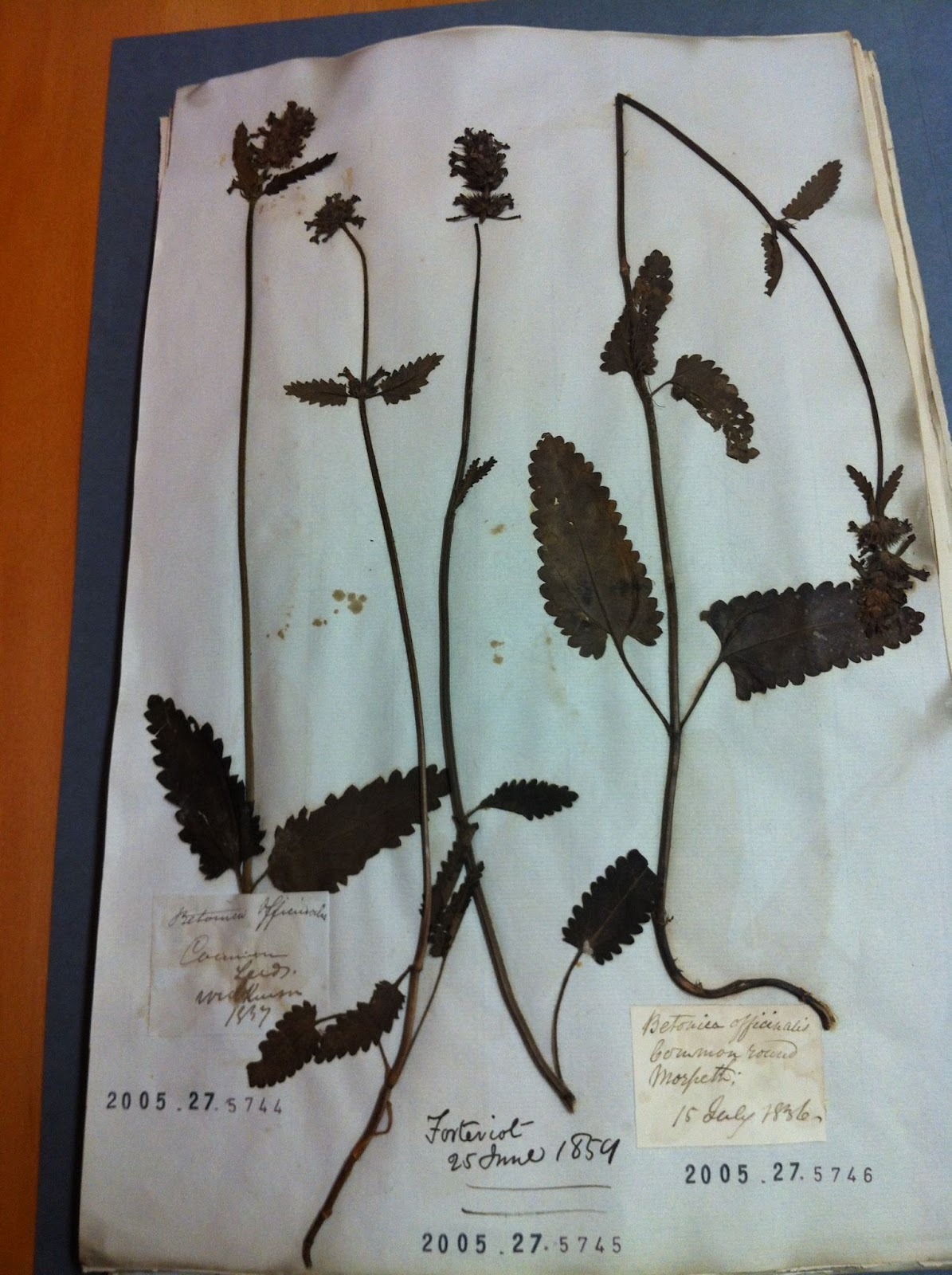

The idea was an immediate success. The society he founded, later joined by the Edinburgh Botanical Club, became a vibrant hub for exchanging ideas, planning expeditions, and holding scientific debates. These organisations sought to build a practical infrastructure: they established regular meetings, began to systematise herbaria, and laid the groundwork for publishing research. Archives from the period show that the Edinburgh native was the true driving force behind this entire process.

A Career in Teaching

Balfour’s academic career took off in 1841 when he was appointed to the prestigious post of Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow. He replaced the distinguished William Jackson Hooker, who was leaving to become Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. This marked the beginning of a period where Balfour honed his teaching methods. Under his guidance, weekly Saturday field excursions were introduced, designed to teach students how to combine theory with practice.

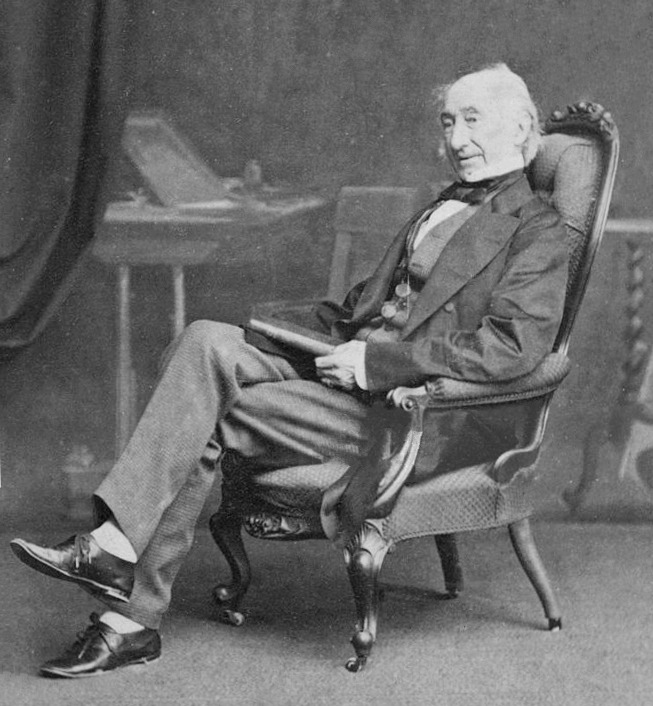

But his true triumph was yet to come. Following the death of his former mentor, Robert Graham, several key botanical posts in Scotland became vacant. Balfour was appointed to fill all of them. He now held the titles of Professor of Botany, Regius Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, and Her Majesty’s Botanist in Scotland. In effect, the Edinburgh native was now in charge of both the academic and practical sides of the science. This consolidation of roles had a dramatic impact. While his early lectures had around 160 students, 33 years later, that number had grown to 400. Over his entire teaching career, he taught 8,000 students, fostering a generation of researchers capable of both scientific and philosophical thought.

An Innovative Approach to Teaching

Balfour’s true genius lay in his ability to impart knowledge. He staunchly refused to simply recite dry lists of species. Instead, he presented botany as a comprehensive discipline covering the structure, function, and distribution of plants. His lecture material was delivered with a pioneering ‘multimedia’ approach, using enormous, detailed wall diagrams, live specimens from the glasshouses, and a vast collection of over 14,000 botanical items. To make complex plant anatomy understandable, he acquired French educational models (from makers like Auzoux and Brendel), which could demonstrate the tiniest details, from stem cross-sections to internal seed structure.

Learning was not confined to the university walls. Balfour effectively turned the whole of Scotland into his lecture hall. The “field” became as much a classroom as the lecture theatre. His demanding schedule included 65 formal lectures and 12 exams or demonstrations, all in addition to his numerous field excursions. The benefit? Students learned to identify organisms in their natural habitat and analyse diverse ecosystems, gaining invaluable first-hand experience.